Grieving a Missing Cat: When Your Indoor Siamese Doesn't Come Home

The hum of the computer monitor usually gets drowned out by that demanding, raspy yowl Siamese cats are famous for. But today, the only sound in the home office is the click of the keyboard and the radiator hissing in the corner. You keep glancing at the beige wool rug near the window—the one that’s usually covered in cream-colored fur—expecting to see that dark chocolate tail twitching in the sunbeam. But the rug is clean. It’s perfectly, agonizingly clean.

That cleanliness feels like an accusation.

When a pet passes away, there is a body. There is a vet visit. There is a definitive, crushing ending. But when an indoor cat slips out the door and simply vanishes, you are left with something psychologists call "ambiguous loss." It is a grief with no edges, a wound that refuses to scab over because your brain keeps whispering, “But what if?”

> Quick Takeaways:

> * Ambiguous loss is distinct: It is a suspended state of grief without closure, keeping your nervous system in a constant state of "high alert" that differs physically from mourning a death.

> * The "Indoor" Guilt: Losing a strictly indoor cat carries a specific, heavy burden of responsibility and shame that outdoor cat owners may not experience.

> * Rituals are vital: Without a grave or an urn, creating a physical focal point—like a custom pet memorial—can provide the psychological grounding necessary to process the loss.

> * The "Search Fatigue": It is normal to feel exhausted and even resentful of the search process. This does not mean you love your cat less.

The Unique Torture of "Schrödinger’s Cat"

Most people understand death. They bring casseroles. They send cards. They nod sympathetically when you cry.

But when your cat is missing, the world expects you to maintain hope, while your heart is already trying to mourn. You are living in a real-life version of Schrödinger’s experiment: inside your mind, your cat is simultaneously alive (scared, hungry, needing you) and dead (hit by a car, taken by a predator).

This duality wreaks havoc on the human brain.

We worked with a customer recently—let's call her Sarah—who lost her Siamese, Kai, when a contractor left the back door ajar. She told us that for three weeks, she slept on the living room floor with the window cracked open, terrified that if she slept in her bed, she wouldn't hear his meow. She wasn't sleeping; she was waiting.

This is the physiological toll of ambiguous loss. Your body stays in "fight or flight" mode, pumping cortisol to keep you alert for a reunion that hasn't happened. You can't grieve because grieving feels like giving up. But you can't relax because relaxing feels like negligence.

The "Magical Thinking" Trap

You might find yourself making silent bargains with the universe. If I don't vacuum the hallway, his scent will stay, and he'll come back. If I leave his bowl full, it proves I haven't moved on.This is normal. It's your brain trying to exert control over an uncontrollable situation. But here is the hard truth that few articles will tell you: Your suffering does not increase their safety. Starving yourself of sleep or joy does not act as a beacon to guide them home.

The Heavy Mantle of "Indoor Cat" Guilt

There is a specific flavor of shame reserved for owners of indoor-only cats who escape.

If you own a Siamese, you know they are intelligent, vocal, and often door-dashers. Yet, when an indoor cat goes missing, the internal narrative is brutal: I had one job. Keep him inside. I failed.

You might feel judged by neighbors or people on social media who ask, "How did he get out?" as if you opened the door and invited him to leave.

Here is the counterintuitive insight we need you to hear: Strict containment is not a measure of love; it is a measure of risk management, and risk can never be zero.

We have seen thousands of pet stories come through our studio. We've seen cats escape through screens pushed out by storms, between the legs of pizza delivery drivers, and through dryer vents. The fact that your cat got out is an accident, not a moral failing.

The guilt you feel is actually grief in disguise. It’s easier for our brains to say, "I made a mistake" (which implies we had control) than to admit "Bad things happen randomly" (which implies we are helpless).

When the Search Stalls: Navigating the "Long Haul"

The posters are fading. The Facebook shares have slowed down. The phone has stopped ringing with leads. This is the "Long Haul," and it is often the loneliest part of the experience.

This is where the emotional nuance gets tricky. You might feel a flash of anger—at the cat for running, at the driver who might have hit them, at the neighbors for not looking hard enough. Then, immediately, you feel guilty for being angry.

The Taboo of "Moving On"

There comes a moment—maybe three weeks in, maybe three months—where you catch yourself laughing at a TV show, or you realize you went a whole morning without checking the lost-and-found boards.And then the panic sets in. If I stop looking, am I killing him?

No. You aren't.

- Active Searching: Dedicated time (e.g., 20 minutes a day) to bump posts online, walk the neighborhood, or check shelter lists.

- Living: The rest of your day, where you are allowed to eat, sleep, and exist without the burden of the search.

Creating Closure Without a Body

This is the hardest hurdle. How do you mourn without a funeral? How do you say goodbye when you don't know if they are gone?

Psychologists suggest that in cases of ambiguous loss, we must create our own rituals. We cannot wait for the universe to give us an ending; we have to write one for our own sanity. This doesn't mean you stop hoping. It means you stop waiting.

The Physical Anchor

When a pet dies, we have ashes or a grave. When a pet is missing, we have an empty space.We have found that families cope better when they create a tangible focal point for their love. This is why many people turn to art. It sounds biased coming from us, but the psychology holds up: holding something physical helps ground the abstract emotion.

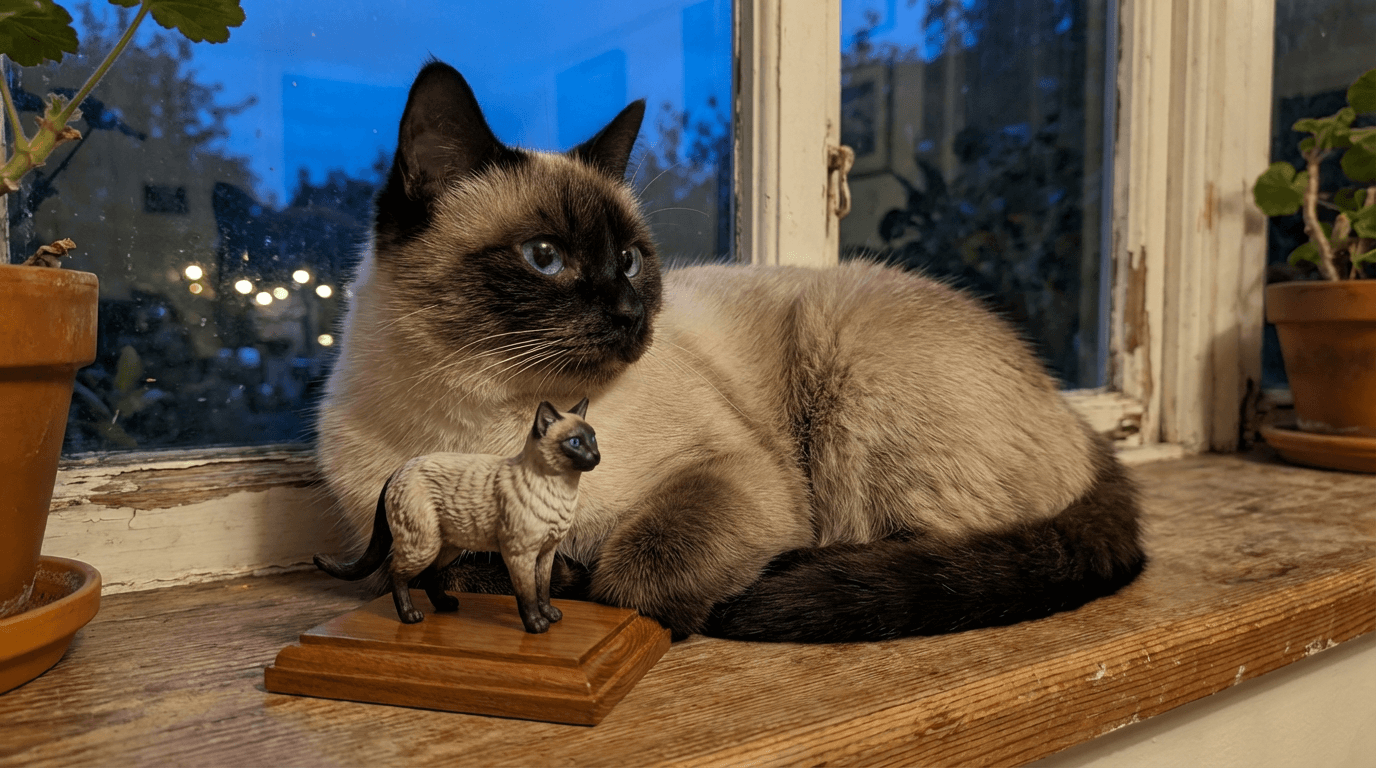

Some families plant a "Hope Garden" in the backyard. Others commission a painting. And increasingly, we see Siamese owners requesting custom figurines not as memorials of death, but as tributes to life.

Having a precise, realistic sculpture of your cat on the shelf gives you a place to direct your thoughts. Instead of staring at the empty spot on the rug and feeling the void, you look at the figurine—the curve of the ears, the specific shade of the points—and you remember the personality, not just the absence. It allows you to say, “I love you, wherever you are,” rather than, “Where are you?”

Coping Strategies That Actually Help

Generic advice like "stay positive" is useless here. You need concrete strategies to manage the anxiety.

1. The "Worry Window"

Set a timer for 15 minutes a day. During this time, allow yourself to spiral. Cry, panic, check every forum, beat yourself up about the open door. When the timer goes off, you must physically change your environment—go for a walk, take a shower, switch rooms. Train your brain that the anxiety has a container.2. Rewrite the Narrative

Instead of visualizing your cat cold and alone (which is torture), visualize them having been taken in by a lonely elderly person who needed a companion. Visualize them living as a barn cat, fed and wild.This isn't lying to yourself; it's protecting your psyche. Since you don't know the truth, you are allowed to choose the scenario that doesn't destroy you.

3. Memorialize the Bond, Not the Loss

Don't let the "Missing" poster be the only image you have of them. Frame a photo of your cat doing something ridiculous—sleeping in a sink, attacking a feather toy. Remind yourself that their life was not defined by how they left, but by how they lived.The Possibility of Return (And the Fear of It)

We need to talk about a feeling almost no one admits: the fear of them coming back after you’ve started to heal.

You might worry that if you get a new cat, or if you pack away the litter box, the universe will play a cruel joke and bring your lost cat home the next day, making you feel like a traitor.

Let’s look at this differently.

If your Siamese comes home after six months (and we have seen it happen—Siamese are tenacious survivors), they won't look at the packed-away toys and think you gave up. They will just be happy to be warm.

Love is not a finite resource. Moving forward doesn't mean erasing the past. You can grieve the cat you lost, love the memory of them, and still make space for peace in your present life.

Closing: The Sunbeam Remains

The home office is still quiet. The radiator still hisses. The rug is still clean.

But perhaps tomorrow, you won't look at the empty rug with panic. Perhaps you’ll look at it and remember the warmth that used to be there.

Grieving a missing cat is a lonely, confusing, jagged road. You are mourning a ghost that might still be breathing. But remember this: the bond you formed is real. It is solid. It exists independently of their physical presence in your house.

Whether they are curled up on a stranger's sofa, prowling a distant field, or have crossed the rainbow bridge ahead of you, they took a piece of your heart with them. And you kept a piece of theirs. No open door can ever change that.

So, take a breath. Turn off the porch light if you need to. It’s okay to rest.